Your password has been breached!

'Your password has been breached!' is a sentence that nobody likes to read after logging into a respected online service. Instinctively, my mind turns to phishing when I do hear it.

Has my telephone provider been hacked? It seems unlikely, but not impossible. Yet, there's a much more plausible explanation.

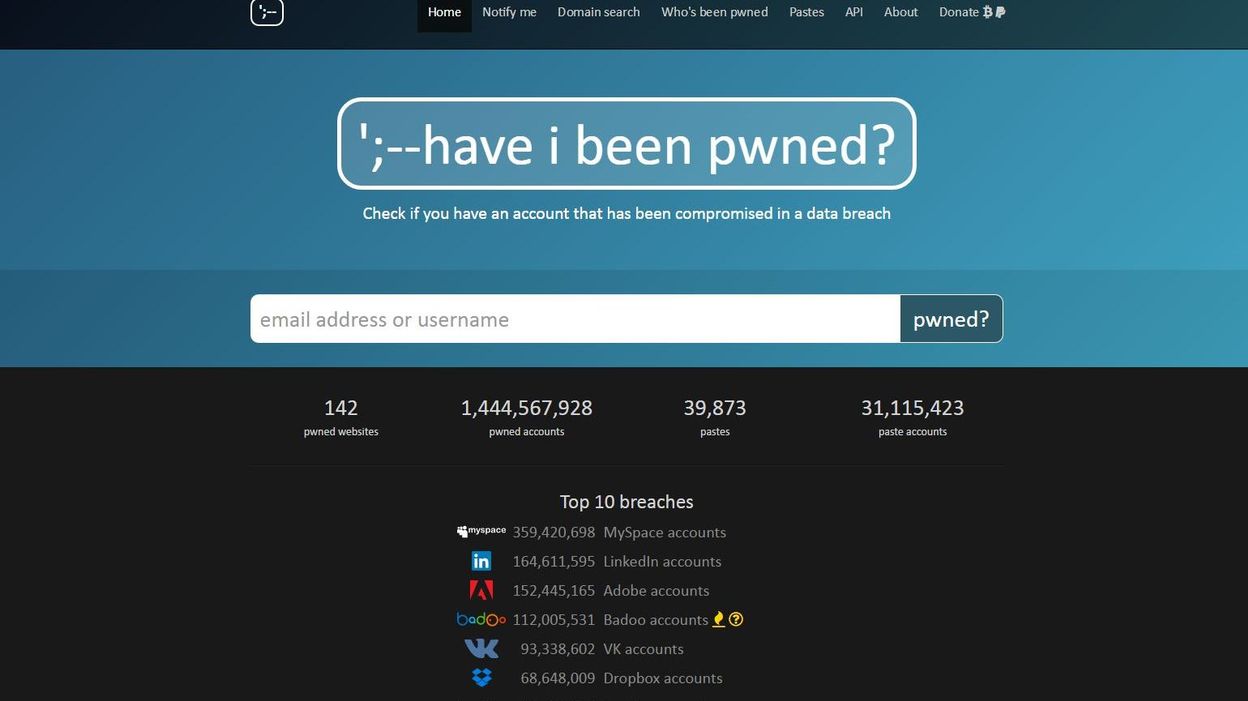

Haveibeenpwned (HIBP)

Meet Haveibeenpwned (HIBP). This project gathers data from leaked password breaches and makes sure that you can easily detect whether (part of) your data was compromised in one of those breaches.

Image source: RTBF.be

How does that work? Well, there are a couple of things you can do on haveibeenpwned.com:

- Verify if your e-mail address or phone number was part of an exposed data breach.

- Verify if your password was part of an exposed data breach.

- Subscribe to get notified if your e-mail address is part of a future data breach.

- Verify if any e-mail addresses that belong to a specific domain (which you control) have been part of an exposed data breach. This will also subscribe you to notifications on future data breaches.

- Review the full list of data breaches including the organisation's name, the breach date, the number of compromised accounts and the type of data that was compromised.

Just head over there and try it out! Just make sure to come back when you're done playing and find out how this all works behind the scenes.

History

Great! You're now aware that there is a free online service that can make you aware of any vulnerable passwords you might be using. If you haven't subscribed yet to get notified when your account is compromised, now is the time to do so!

Before we dive into the inner mechanism, let me give you a brief history:

- Haveibeenpwned was ceated in August 2017

- Run by Troy Hunt

- Finds its origin in the recommendation of NIST to check user-provided passwords against existing data breaches.

Where is the data coming from and where can I see it?

- Data includes breaches from companies such as Canva, Datacamp, Deezer, Domino’s, Ethereum, Linkedin, Mastercard, Minecraft, Oxfam, Sitepoint, Snapchat, Twitter and many many more. The full list is available on the website.

- The full data set can be downloaded freely via Cloudflare or torrent. Version 2 of the data set was 8.75GB large and included over 500 million breached password hashes.

- Next to the functionality on their website, there is a public API that allows you to easily access all this data programmatically.

Overall, it is a simple yet extremely effective project with a web interface which is easy enough for anyone to understand the benefits.

Concerns

At this point, you might be asking yourself:

Is it safe for me to enter my password on any website besides the one for which the password is used?

No, it's not. You should avoid this at all cost. The author also encourages you to develop your own tooling based on the full data set which you can download. In that way, there is no need to enter your password anywhere outside of your own environment.

And even if we assume HIBP can be trusted, entering your password there still poses risks:

- The request could be intercepted by a malicious actor.

- Requests are cached via Cloudflare so a third party is involved in the process.

API v1

When v1 of the public API came out, there was another concern for companies that wanted to inform their users of a leaked password. They did not want to block users from taking action (account creation, platform transaction ...) simply because a password had already been leaked.

It also allowed for direct password searches, meaning you could trigger a GET request to /pwnedpassword/{password} to find out if it had ever been leaked.

API v2

Despite no longer being active, v2 might have introduced the most important pillar of this API: k-anonimity. In terms of this project, it can be described as a solution to solve the problem:

'How can we guarantee that a request to this API which includes (part of) a (hashed) password does not allow an attacker to identify that same password?

Let's say I'm an attacker and I somehow managed to find out that you have made a request to /pwnedpassword/cbfdac6008f9cab4083784cbd1874f76618d2a97. If I run this last URL segment against my rainbow table, I'll quickly discover that you were trying to check if password123 was ever leaked.

The solution? Searching for a partial hash.

Re-run the previous scenario but with the first 5 characters of the hashed password: cbfda. The API now no longer returns if there is a match, rather it returns a list of suffixes for cbfda. For example:

00791BB54CC9122C70C1156FD97134EB83E:3

008CDEBE10E31BF09C9BD20CBCC2C9CEDA3:2

00BD64FF4BE8674BC4C85CE380856184F9C:1

014BD2A0B6A9CE1553A4E1F48F57A88B40A:1

018976509BD8782F7B991A1B559150A504B:1

...

C6008F9CAB4083784CBD1874F76618D2A97:251682

...

FE80167C035EBF78700BB71DA158EF7AEE8:1

FF1F0EE2B4978AB1F6588451DE34F06B3E0:1

FF6F85C4A6F4AA0E0DEB953DF370379DABB:1

FFCF30D7BA01CFC1D21E888E3AC67726085:2

FFFB48B574F158C0C05FB297FB30933FA09:1

The full list contains 855 results. Meaning: as an attacker, even if I manage to extract all 855 matches from my rainbow table, I have no clue which of these 855 passwords you are searching for.

But the response is still useful for you because you can easily verify if one of these matches with the suffix of the password that you were actually looking for. And guess what? C6008F9CAB4083784CBD1874F76618D2A97 matches!

But what does the number behind the colon mean?

Oh, you mean 251682? That's the count of passwords that match this hash across all breaches. So please don't select password123 as your password!

Side note: I love Troy's article on API versioning and his reasoning behind it. A must-read!

API v3

Are you still reading? Don't worry, we're almost there.

v3 is the current active version. It didn't contain changes to the interface for password searches but did:

- include a 3% increase in new passwords. Meaning: passwords that had never been detected in previous breaches.

- include 194 million new records of breached data. Meaning: the total count (see above) increased by 194 million.

- improve data integrity. Meaning: imagine managing a database with over 500 million records coming from sketchy sources. Or don't, because it sounds like a hell of a job.

Use cases

There's no doubt about it: HIBP has massive potential. But who's using it and why?

On the one hand, we have individuals who can perform one-shot detection of any leaked password. Or they can subscribe to the monitoring service and get notified when there e-mail address is found in the data of new breaches.

Similarly, organisations can protect their users by notifying them if their selected password has been leaked. And they can monitor new breaches for e-mail addresses with their domain name. Sounds great, right?

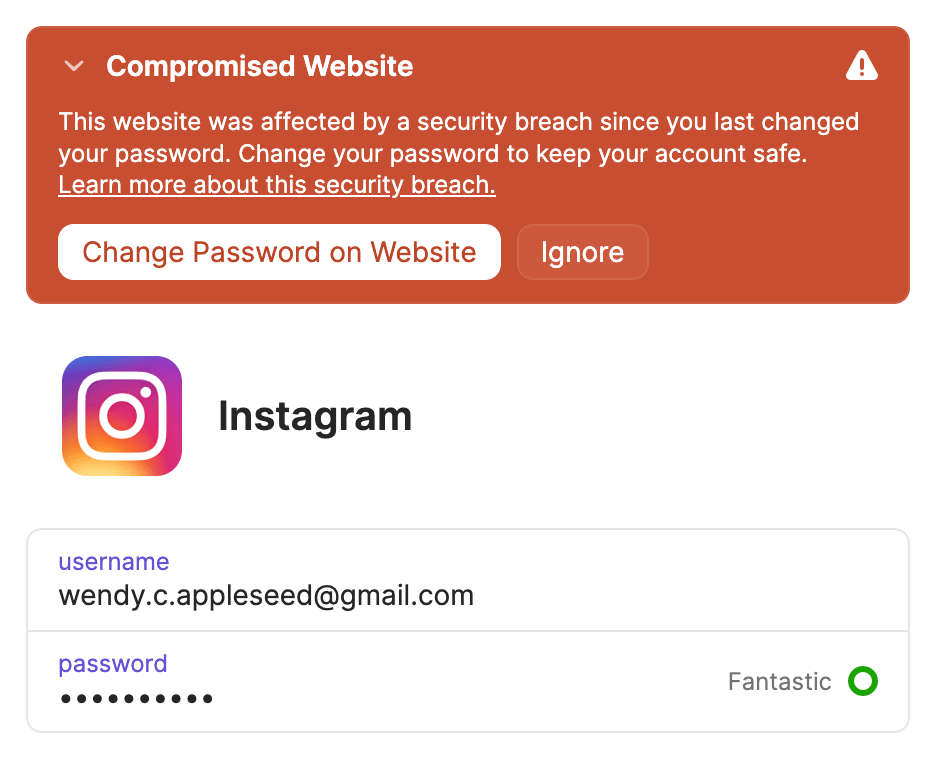

And who better to make use of all of this than a password manager? Most notably, 1password integrated HIBP into their Watchtower dashboard.

Image source: 1password

Even better: law enforcement agencies also jumped on the bandwagon. Most notably, the FBI can feed hacked passwords directly into the password database. And national agencies can (and did) promote and contribute to HIBP as part of their prevention strategy.

Conclusion

Ever since Mobile Vikings (a Belgian telco provider) notified me that my password had been leaked, I have been fascinated by the simplicity and effectiveness of HIBP.

It took me a while to dive into the details but I learned so much. But most importantly, HIBP is living proof that if you can provide significant value for others, small ideas can turn into enormous projects backed by powerful organisations.

And on that bombshell: good night!